Polish Portsmouth

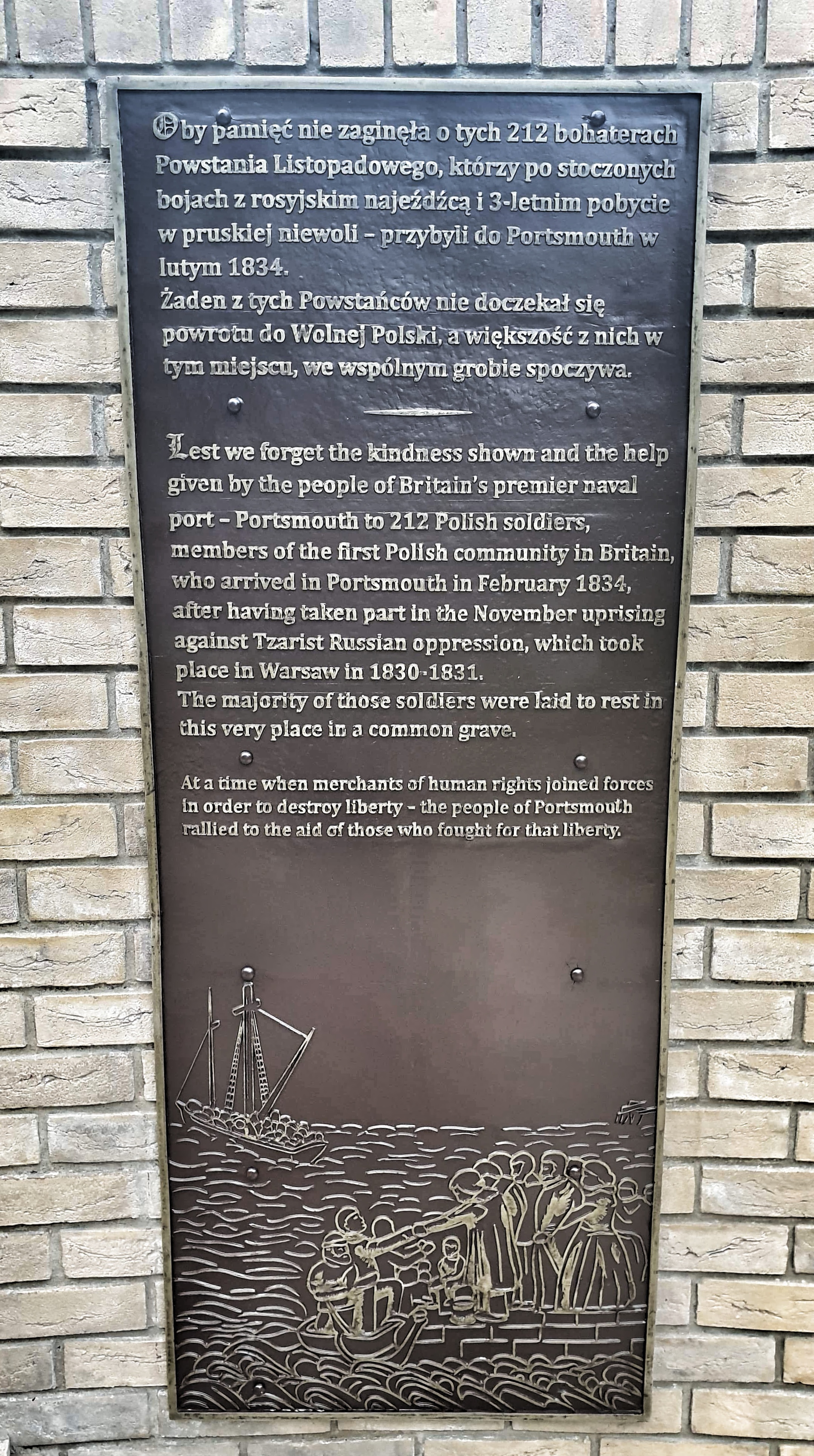

In the Winter of 1833/34, the Prussian ship Marianne was travelling westwards across the North Sea. On board were 212 Polish soldiers who had been expelled from their homeland and were en route from Gdańsk to America. Weather conditions, however, quickly deteriorated and in the face of high winds and heavy seas the ship’s Prussian Captain was forced to seek shelter, eventually docking in Portsmouth.

When the plight of the Marianne reached the attention of local newspapers in February 1834, it had been in dock for five weeks and relations between the German crew and their Polish ‘cargo’ were, to say the least, tense. By this time, the winds had decreased and the ship was ready to continue its journey. With the anchor on the point of being raised, however, the Poles had forcibly taken possession of the vessel. So violent and threatening was their behaviour, the Captain claimed, that fearing for his own life, he had been forced to apply to the Civil Authorities for protection.[1] This version of events was hotly disputed by the Poles who alleged that Prussian agents had deliberately removed food and water supplies from the Marianne in order to force the soldiers to agree to depart for America. Eventually, following pressure from the legal courts in Portsmouth, some sort of a deal was reached and on 14 February the Poles disembarked from their ship and were transferred to lodgings on land.[2]

The situation in which they found themselves was an unpropitious one; they had no food, no money, no guaranteed shelter and no knowledge of England and its language. Indeed, the majority of them were unable even to read or write in Polish. Their legal status, meanwhile, was uncertain and various schemes for their removal and repatriation had been suggested. The soldiers’ welcome in Portsmouth, nonetheless, was a warm one. A report circulated in early March 1834 noted that ‘they had been treated with much hospitality by the greater part of the inhabitants, who daily visit them to administer to their comforts, and alleviate their forlorn situation.’[3] Further support was provided through a series of hastily arranged fundraising activities. On 7 March, a ‘very gratifying and highly respectable’ charitable musical evening was organised at the Rainbow Tavern in St. George’s Square, featuring ‘patriotic and spirited sketches and songs’ by a Mr Woolfe; these were received with enthusiastic applause.[4] Two of the Polish soldiers attended the event and performed ‘some native Polish songs.’[5] Later, speaking through a translator, the soldiers addressed the assembled audience to express their thanks for the support they had received.[6] The Forensic Society, meanwhile, a popular group which put on mock legal trials, organised a special fundraiser for the Poles which attracted ‘nearly 500 people.’[7] Their efforts were helped by the gas company (which lit the room), the printer of the tickets, the doorman and the trumpeter who all provided their services free of charge.[8] A Polish concert organised at the Assembly Room attracted an even larger audience and raised over £60 – the equivalent today of in excess of £4,000.[9] Further events were put on by the Choral Society and the city’s theatres.[10] The great and the good from across the city, meanwhile, queued up to make donations. The MP J.B Carter subscribed £5 and 5 shillings[11], the Reverend R.B Sibthorpe gave £5[12] and Lady M.E. Lindsey £3.[13] An anonymous donation of £25 was received from an individual described ‘as a friend to Poland.’[14] Many others followed suit. Particularly noteworthy were the efforts of the city’s children; by the beginning of March 1834, £14 and 7 shillings (around £1,000 today) had been raised through the combined work of four schools.[15] Eventually, this piecemeal, local support was supplemented and replaced by more official forms of relief. In June 1834 Parliament agreed to provide £10,000 to assist Polish refugees across the country, and the following month the Portsmouth Poles were moved into semi-permanent accommodation at the former Old Garrison Hospital in Portsea. The enthusiastic support Portsmouth provided for its Polish visitors, however, did not go unnoticed. At ‘A Meeting for the Relief of the Polish Refugees’ in London, the politician, Lord Dudley Stuart, to loud cheers from the assembled audience, praised the good work of the people of Portsmouth and the surrounding area.[16] The MP Cutlar Fergusson speaking at the same event concluded that ‘the Conduct of the Inhabitants of Portsmouth could not be spoke of too highly.’[17]

Such activities raise a number of questions about Anglo-Polish relations, foremost among them: why were the residents of a provincial English city willing to provide such enthusiastic support for refugees from the other side of Europe? For much of the eighteenth century, the British public had shown little interest in Poland. And when the country was discussed, the focus was generally on the nation’s, to British eyes, highly eccentric political constitution, particularly its elective monarchy and its liberum veto, the infamous mechanism through which any member of the Sejm (Parliament) could veto an act of legislation. Such accounts were invariably critical in tone and premised on a comparison between British advancement and Polish backwardness. The abuses Poland was to suffer at the hands of its neighbours, however, did much to alter perceptions. 1772, 1793 and 1795 saw a series of progressively more extensive partitions, whereby Prussia, Austria and Russia worked in concert to annexe Polish territories. Under the terms of the final partition, Poland lost all its remaining territories and, as such, ceased to exist as a political entity. The elimination of a twelve-hundred-year-old state from the map of Europe received extensive coverage in the British press, as did the actions of the Poles who resisted the partitioning powers. Tadeusz Kościuszko, the leader of the heroic, although ultimately unsuccessful, armed uprising of 1793/4, quickly became a household name in Britain. Poets, among them Samuel Taylor Coleridge, John Keats and Lord Byron, celebrated his bravery in verse, while Kościuszko’s visit to England inspired both a portrait from the celebrated artist Benjamin West and a hugely popular novel, Thaddeus of Warsaw, by the Scottish writer Jane Porter.[18] The November Uprising of 1830 and the war with Russia that followed prompted an even more wide-ranging response; the vast majority of which was sympathetic to Poland and critical of the actions of the Russian Tsar, Nicholas I. The main incidents of the war were described in detail in both the local and national press, and a series of short introductions to Polish history were published for those who desired further information. Two journals, albeit both short-lived, were launched specifically concerned with Polish affairs – Polonia and The Hull Polish Record – and translations of the works of Poland’s national poet, Adam Mickiewicz, were published in Britain for the first time in 1830.[19] A series of public events followed in which praise was lavished on the ‘brave Poles’ and their noble cause. During a well-attended meeting in Blackfriars in January 1831, they were described as ‘the vanguard of the heroes of liberty.’[20] At a public dinner at the Crown and Anchor pub in March of the same year, those present drank to ‘the Independence of Poland, violated by fraud, may it be restored by valour, and cemented by liberty.’[21] Taken collectively, such representations produced a sea-change in British attitudes. Indeed, speaking in 1848, Dudley Stuart concluded that whereas in the 1820s little was known about Poland, the events of the early 1830s had ensured that ‘Polish affairs [were] comparatively familiar to the minds of all men in this country, and had excited so much the sympathy of all mankind.’[22] This sympathy, it is true, was never to produce any direct British action aimed at re-establishing a Polish state. However, when a group of Poles washed up in Portsmouth in the Winter of 1834, the people of the city had firm preconceptions about them and their cause. These soldiers had fought against the Russians in the uprising of 1830/1 and, after fleeing on to Prussian soil, had been held in a Prussian prison for two years. As a consequence, they were not simply anonymous refugees from a far-away land. Rather, it was agreed, they were victims of the tyranny of Russia, Prussia and Austria, and upholders of the values of courage and liberty with which Britain sought to associate itself.

In the years that followed, the Poles continued to inspire both interest and sympathy from the residents of Portsmouth. The 1835 funeral of one of the refugees, named in the press as ‘Jozef Marrejouski’, was attended by ‘all his comrades’ and many gentleman of the town; music for the procession was provided by the Royal Marine band. A report in the Hampshire Advertiser concluded that the service had made a ‘deep impression on the numerous spectators.’[23] In December of the same year, ‘several respectable families and inhabitants’ from Portsmouth attended a celebration at the Polish Barracks of the anniversary of the 1830 Uprising. There was music, singing and dancing, and the same Mr Woolfe, who had contributed patriotic songs for the fundraiser in 1834, wrote a new ditty entitled ‘The Warriors of Poland shall be free.’[24] Despite such support, however, Anglo-Polish relations did not always run entirely smoothly. Ironically, some of the difficulties the émigrés faced were a direct by-product of the high esteem in which Poland’s cause was held. From the mid-1830s onwards, reports circulated in the press about the existence of ‘fake’ Polish Patriots. Among the most successful of these individuals was a Captain Gordolphl – nicknamed ‘the Magnetic Pole’ on account of his ‘fascinating manners’ – who, until the police intervened, was employing forged certificates and passports to extract sympathy – and money – from the people of Glasgow.[25] The presence of such impostors clearly alarmed the Poles of Portsmouth, and the highest-ranking officer based in the city, Captain Stawiarski, wrote to the Hampshire Telegraph in May 1842 to remind readers that all Poles who were of ‘good character and conduct’ received an allowance from the government.[26] Consequently, he noted, anyone who applied for ‘relief’ on the streets was an impostor.

Other problems emerged as a result of indiscipline. In March 1835, a fight broke out among the Poles at the Garrison Hospital in which one of the soldiers was injured by a group of ‘six or eight others.’[27] Warrants were later issued against all parties and the case was brought before the Borough Court, only to break down because of a failure to find a competent translator. The soldiers were let off with a warning. Seventeen months later, one of the refugees, Joseph Rozański, was arrested on charges of assault against a local woman, Ann Newberry.[28] The case was made even more serious by the fact that when the Constables went to the ‘Polish Barracks’ to issue the arrest warrant, they were violently resisted by the other Poles, who seized Rozański from them on multiple occasions. While not guilty verdicts were handed out to two individuals prosecuted for assaulting the police at the trial that followed, Rozański was convicted and sentenced to six days in prison. This incident prompted heated discussion in the local press. A correspondent writing just after the initial incident noted that it was ‘a disgrace to this country’ that while British workers were unable ‘to gain a livelihood by the sweat of their brow’ ‘a set of foreigners […] can afford to get drunk nightly, and kick up rows in our street.’[29] The Hampshire Telegraph, meanwhile, concluded that the soldiers were ‘a disgrace to the neighbourhood and themselves.’[30] Attacks against the Poles became, meanwhile, even more frequent amidst the political unrest and social upheavals of the 1840s. Perhaps the most virulent was that developed by the Scottish politician, the Earl of Eglinton. Speaking to the House of Lords on 19 March 1849, he drew attention to the large medical bill that had been wracked up by Polish refugees in London and Portsmouth, implying, non-too-subtly, that this was a result of endemic syphilis.[31] Eglinton then went on to develop an angry general attack on the Polish diaspora, noting that in every incident of unrest across Europe this ‘lawless and turbulent group’ were to be found ‘revelling in scenes of anarchy and blood.’ Given that Britain’s finances were in a dire state and its people starving, should the government, he asked rhetorically, continue to fund such a people? Ultimately, Eglinton’s core accusation proved entirely unwarranted; an investigation concluded that there had only been one case of venereal disease among the Polish community in the previous year. And summarising the findings, the Marquis of Lansdowne concluded – to cries of ‘hear, hear’ from the Lords – that ‘he was satisfied of the general morality and conduct of the Polish exiles.’[32]

Claims that Poles were engaged in subversive political activity, however, proved harder to discredit, not least because they were, in many ways, accurate. This was particularly true in relation to the refugees based in Portsmouth. On their arrival, they had been contacted by various monarchist, liberal and socialist Polish émigrés already active in England, who were anxious for new converts to their particular vision for a future, ‘free’ Poland. Ultimately, it was the latter group who gained the ascendency; and in November 1835 the soldiers formed their own political organisation, Lud Polski (The Polish People), and issued a radical manifesto.[33] Central to this document was an angry critique of the role which the nobility had played in Polish history. ‘Our fatherland’, the manifesto proclaimed, ‘that of the Polish people, was always separate from the fatherland of the nobility, and if there was contact between the two, it resembled that between a murderer and his victim. Throughout the world a sea of blood divides the gentry from the people.’[34] To rectify this situation, a violent revolution was required, which would sweep away the old order, and replace it with a system based on the collective ownership of the nation’s resources. This initial document was signed by 133 of the Polish soldiers who styled themselves ‘The Grudziąż Commune’, the name deriving from the town of Grudziąż where they had been incarcerated prior to their arrival in England.[35] Other Lud Polski communes emerged first in Jersey, where the leading intellectual lights of the movement settled, and later in London. Over the following years, the Portsmouth group produced a wide range of polemics, entering into correspondence with both the other Lud Polski communes, and radical organisations and political leaders across Europe. At the same time, while initially reluctant to engage in English political debate, in the 1840s they took on a more public role in their adopted homeland. This culminated in a letter, published on 20 November 1841, to the Chartist newspaper The Northern Star.[36] In this address, the Poles criticised the treaty Britain had entered into with Russia, Prussia and Austria the previous year, and invited the people of England to join them at Portsea to commemorate the anniversary of the November Uprising. This Uprising, they claimed, was not just a Polish issue. Rather, it was an ‘event which by the dispersion of the free people [i.e. the Poles who took part in the revolution] among all the oppressed people of the world, was […], in the hands of providence, the means of uniting their mutual interests into one common and indissoluble bond: an event which, perhaps, was but the precursor of the general freedom of mankind.’ The Lud Polski organisation was eventually wound up in 1846, having achieved little to foment either Polish liberation, or a wider social revolution. Its vision of a class struggle between peasants and landed gentry, its ideas for the division of property and, more broadly, its advocacy of a form of socialism specifically concerned with the injustices of serfdom were, however, to prove significant. Indeed, for the historian Peter Brock, it was in the activity of the Lud Polski movement that ‘the history of revolutionary populism in Eastern Europe begins.’[37]

Such achievements give the activities of Portsmouth’s Polish community an important place in the development of socialist politics. However, at a day-to-day level, the evidence suggests that the Poles found life in Portsmouth a challenge. Many were resident in the city for a relatively brief period of time. By 1849 only 73 (of the original 212) Poles were living in the area, and by 1860 it was just 35.[38] A number of these individuals moved to other English cities, some sought a new life in America, others, it can be assumed, managed to return to Polish territories. Of those who remained, the majority lived out the rest of their lives in relative poverty as pensioners of the British government, first in the Military Hospital and later in a series of shared houses in the Portsea and Landport districts. These individuals, it should be remembered, many of whom were in their 40s on arrival in Portsmouth, had already endured much suffering. They had been agricultural serfs in their youth, seen violent military action in the November Uprising and, later, endured captivity in a Prussian prison. They had also completed a doubtless terrifying journey across the North Sea in high winds and heavy seas. It was, perhaps, unsurprising that after such experiences they turned, in a sense, inwards and sought solace in drink and the company of their fellow countrymen.[39] Other individuals did, however, come to engage more directly with the local area and its residents. Tomasz Lepik, for example, formerly a sapper in the Polish army, gained a living in Portsmouth as a tailor and, in 1839, married the daughter of a local upholsterer, Sarah Ross. They had their first daughter in 1841 and went on to have nine further children. By 1861, Thomas, Sarah and their three eldest daughters were all working in the cloth trade. Michał Kisielewski, meanwhile, appears to have married into the same extended family, wedding a Mary Ann Ross in 1838, also the daughter of an upholsterer. Michał went on to become a tailor, while his eldest son, Alfred, worked as an upholsterer, and a younger son, William, served in the Royal Navy. Michel himself died in Portsmouth in 1882 at the age of 74.[40]

Polish names, albeit often horribly misspelt, continue to appear in the census and in the birth, marriage and death registers for Portsmouth throughout the nineteenth century. Within more public records, however, such as newspapers and periodicals, Poles feature increasingly infrequently. In part this was a product of the dwindling size of the group; by the 1850s and 1860s many of the original group of soldiers were reaching the end of their natural life spans. Equally importantly, however, Portsmouth had become accustomed to its Polish residents. While the refugees’ political beliefs remained radical, they were no longer the exotic, glamorous revolutionaries they had been thirty or so years previously, but rather an established presence in the city.

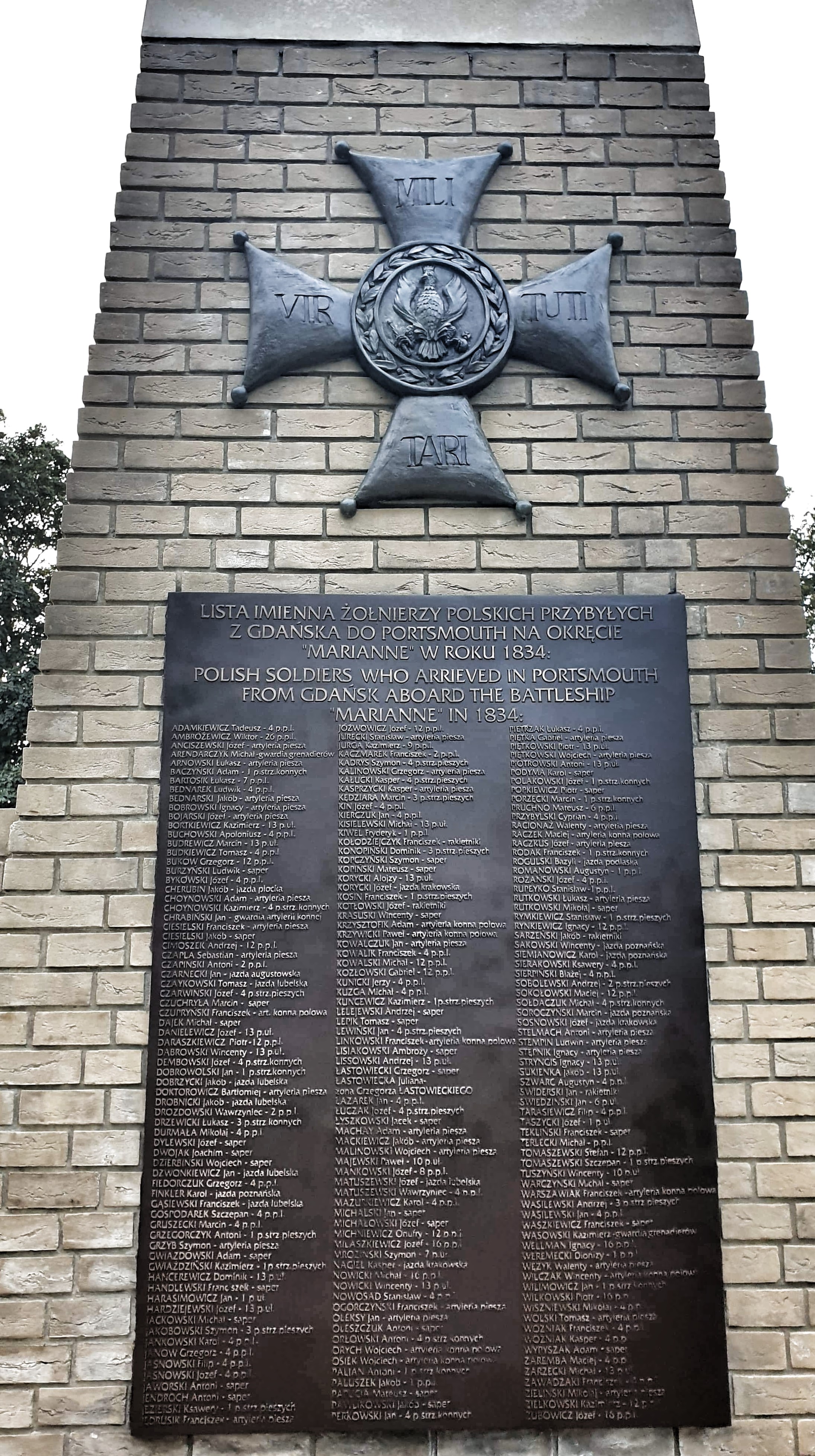

In the 1960s, a committee was established to construct a monument to commemorate the achievements of Portsmouth’s first Polish community. However, while building work began in 1965, funding soon ran out and the project was suspended with the monument unfinished. It was not until the twenty-first century that, under the direction of the Polish war hero Colonel Otton Hulacki, a soldier in General Anders’ 2nd Polish Corps and a participant in the Battle of Monte Cassino of 1944, the committee was revived and work recommenced. Thanks to the efforts of Major Hulacki, the Monument to the November Insurgents was completed in 2004 and unveiled in a ceremony at Kingston Cemetery, Portsmouth on 27 June of that year.

Images: Agnieszka Michalska

Words: Ben Dew (ad6235@coventry.ac.uk)